To many, Latchingdon is just a place you pass through to get to somewhere else – Mayland, Bradwell, Southminster or Burnham.

In that respect, the B1018 does it a huge injustice, for the village has a special character, community and heritage all of its own.

Its written story begins with pre-Domesday ‘Laecedune’ – “a well-watered hill”.

That hill, the very first settlement, was probably a good mile from the centre of the present village, on high ground near the moated, early-16th Century Tyle Hall, alongside the Lower Burnham Road.

That would certainly make sense for, not far away, is the former (first) parish church of St Michael.

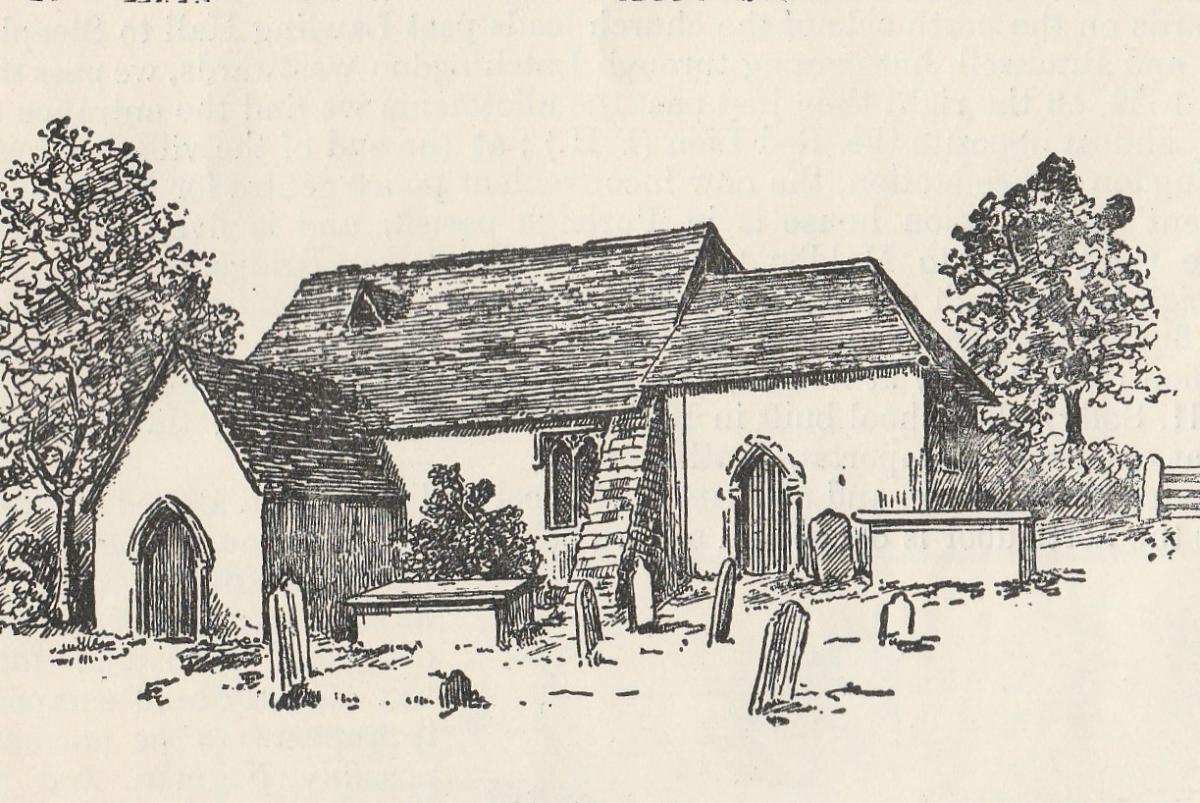

Controversially converted into a private house in 1976, the surviving building is at least 14th Century, but doubtless stands on the site of an earlier place of worship.

By the time the Domesday survey was taken in 1086, the lands of ‘Lachentuna’, as it had then become known, were removed from the old Saxon guard (including Alwine and Leofwine) and divided between the King (William the Conqueror), the monks of Holy Trinity, Canterbury, and a mysterious woman called ‘Wulfgifu’ – the 'wife of Fin' (whoever he was).

Mention is made of woodland, meadows and pasture – the origins of what is still essentially a farming parish.

As time progressed manors and farmsteads emerged, including the still familiar Lawling (which could actually be the ‘Lellinge’ once owned by Ealdorman Byrhtnoth of Battle of Maldon fame), Snoreham (at least 13th Century and once with its own church), and Uleham’s Farm (the gloriously named 'owl haunted place', farmed by the Bugg family in the 19th Century).

Then we have Marsh House (the home of Walter ate Mershe around 1319), Stamford (occupied by William de Stamford in 1332), Tinker’s Hall (home to Hugh and Avice de Tykencote in 1318), Arley Grange (where John Ardeliegh lived in 1380), Bridgeman’s Farm (John Bregman farmed from there in 1310), Good Hares (after John Goodhare in 1375), Lawling Smiths (the forge operated by John the Smith in 1310), and Merchants Farm (after Philip le Merchant, 1247).

Brook Hall is 'le Broke' in 1310, Hill Farm is 'Hellhouse' in 1557, Hydemarsh 'le Hyde', and Tyle Hall is 'Teylede' around 1320 (the seat of the wealthy Osborne family in the 16th Century).

Then we have the first mention of a 'Red Lion' (as in the farm) depicted on Chapman and Andre’s survey of 1777. Although other hostelries (like the now long-gone Engineer’s Arms) have since closed, the pub of that same name, the Red Lion, is, of course, still there and has a list of past landlords going back to Elizabeth Taylor in 1839.

She doubled as the postmistress and her family continued with the licence until the end of the 1880s.

By that time Latchingdon, with its weather-boarded dwellings (my favourite is Grade II listed ‘Chestnuts’), had its own school (built in 1852), police station and magistrates' court (opened in 1842 and now a private house), and a new church.

The old church of St Michael had become disused (except as a mortuary chapel) and ruinous – even its tower had fallen down.

The site for its successor, Christ Church, confirmed the shift of the official village centre.

Built of Kentish Ragstone in 1857 to the designs of architect James Piers St Aubyn (1815-1895), it has a steep roof with a distinctive bell cote.

Richard Formby was vicar there from 1859 to 1895 and there is a stained glass window dedicated to him and his wife.

Rev Formby ministered to a population that had remained relatively stable at around 400 to 500 (actually 394 in 1813, 451 in 1831 and 549 in 1887 – it was 1,241 in 2011).

Going through the census returns, the Victorian residents largely consisted of agricultural labourers, their farmer/employers, stockmen, bailiffs and grooms, but also the odd boot-maker, fishmonger, beer house-keeper, servants, teachers, a dressmaker, thatcher, blacksmith and even a mole-catcher.

Some of those families would go on to lose members during the Great War – eight of their names are listed on the war memorial.

Neither did the village avoid the ravages of the Second World War of 1939-45, with a staggering 250 bombs, mines and explosives falling on the village.

The locals also saw plenty of dog-fights in the skies above.

On Saturday August 12, 1944, an aircraft experienced engine failure overhead. The American pilot, Lieutenant Jerome E Jahnke, bailed out and landed on a haystack in a field a mile away from Lawling Hall.

Meanwhile his P51 Mustang buried itself into the hall’s farmlands.

Thirty-two years later, in 1976, I helped recover the remains of that aircraft and was privileged enough to meet Jerome, who had come over from the States especially to see the excavation.

That teenage experience, along with visits with my late father to the wonders of Fred Dash’s scrapyard, has resulted in my continuing fondness for Latchingdon and its history.

Not only that, but my favourite exhibit in Chelmsford Museum is part of a 15th Century rood screen, paintings of ten saints that once formed part of the ancient décor of Latchingdon St Michael’s.

You can see two of them – St James the Great and St James the Less – on the Art UK website at artuk.org/visit/venues/chelmsford-museum-3289.

We can say with certainty that the village’s early residents looked upon those same images and, in that respect, all these centuries on we can still connect with them and their 'well-watered hill'.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here